This is part of a series of posts looking into SS7 and Sigtran networks. We cover some basic theory and then get into the weeds with GNS3 based labs where we will build real SS7/Sigtran based networks and use them to carry traffic.

So one more step before we actually start bringing up SS7 / Sigtran networks, and that’s to get a bit of a closer look at what components make up SS7 networks.

Recap: What is SS7?

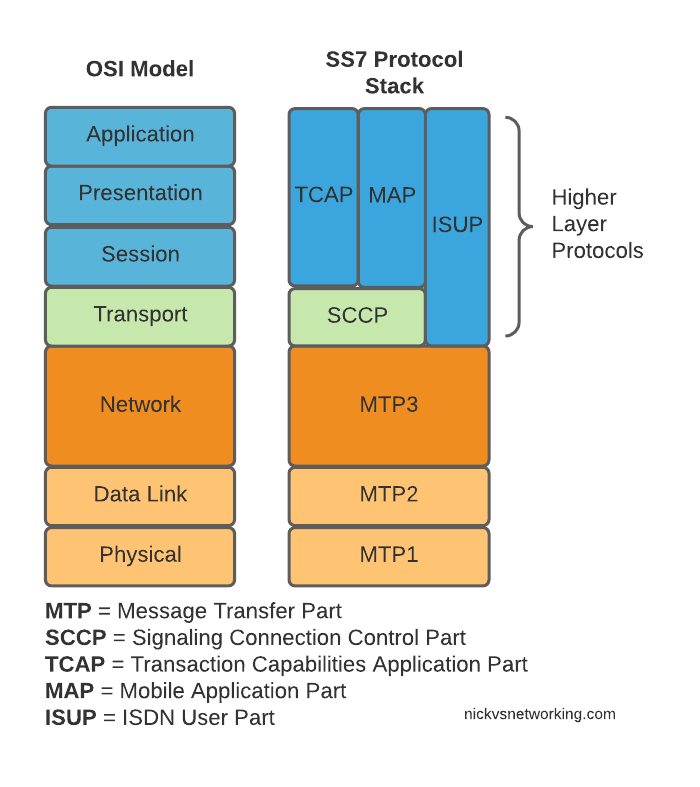

SS7 is the name given to the protocol stack used almost exclusively in the telecommunications space. SS7 isn’t just one protocol, instead it is a suite of protocols.

In the same way when someone talks about IP networking, they’re typically not just talking about the IP layer, but the whole stack from transport to application, when we talk about an SS7 network, we’re talking about the whole stack used to carry messages over SS7.

And what is SIGTRAN?

Sigtran is “Signaling Transport”. Historically SS7 was carried over TDM links (Like E1 lines).

As the internet took hold, the “Signaling Transport” working group was formed to put together the standards for carrying SS7 over IP, and the name stuck.

I’ve always thought if I were to become a Mexican Wrestler (which is quite unlikely), my stage name would be DSLAM, but SIGTRAN comes a close second.

Today when people talk about SIGTRAN, they mean “SS7 over IP”.

What is in an SS7 Network?

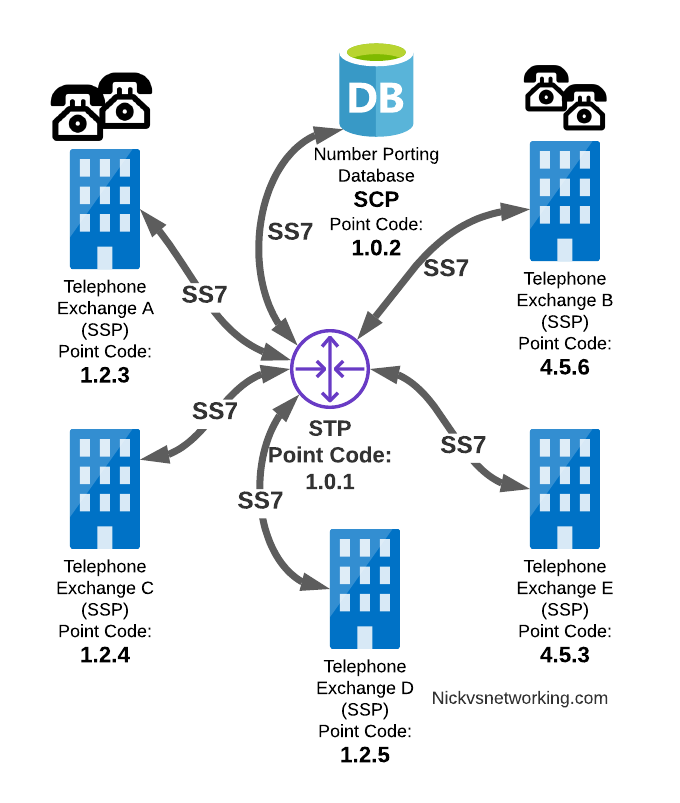

SS7 Networks only have 3 types of network elements:

- Service Switching Points (SSP)

- Service Transfer Points (STP)

- Service Control Points (SCP)

Service Switching Points (SSP)

Service Switching Points (SSPs) are endpoints in the network.

They’re the users of the connectivity, they use it to create and send meaningful messages over the SS7 network, and receive and process messages over the SS7 network.

Like a PC or server are IP endpoints on an IP Network, which send and receive messages over the network, an SSP uses the SS7 network to send and receive messages.

In a PSTN context, your local telephone exchange is most likely an SS7 Service Switching Point (SSP) as it creates traffic on the SS7 network and receives traffic from it.

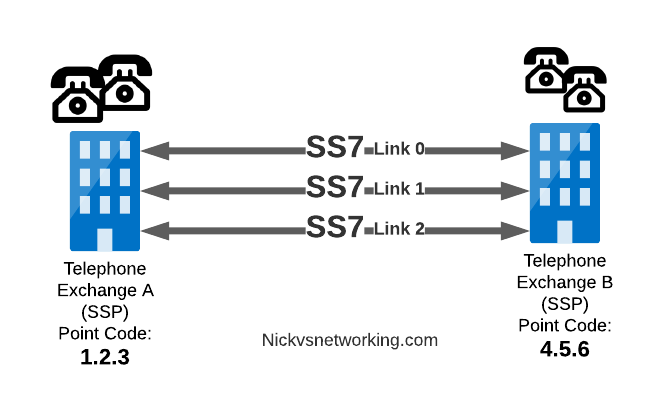

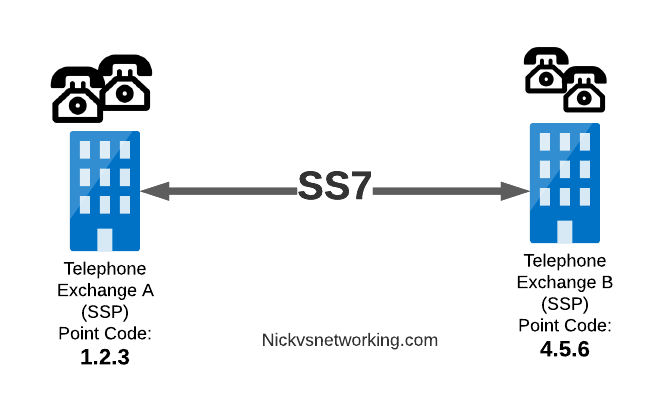

A call from a user on one exchange to a user on another exchange could go from the SSP in Exchange A, to the SSP in Exchange B, in the same way you could send data between two computers by connecting directly between them with an Ethernet crossover cable.

Messages between our two exchanges are addressed using Point Codes, which can be thought of a lot like IP Addresses, except shorter.

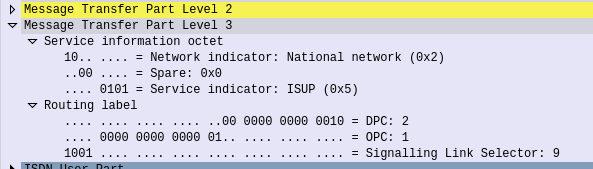

In the MTP3 header of each SS7 message is the Destination Point Code, and the Origin Point Code.

When Telephone Exchange A wants to send a message over SS7 to Telephone Exchange B, the MTP header would look like:

MTP3 Header: Origin Point Code: 1.2.3 Destination Point Code: 4.5.6

Service Transfer Points (STP)

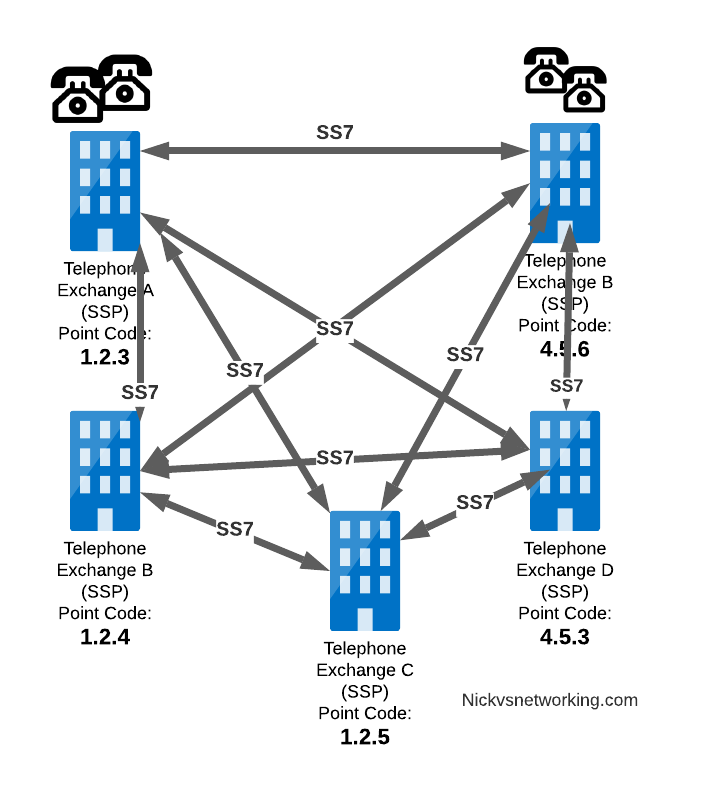

Linking each SSP to each other SSP has a pretty obvious problem as our network grows.

What happens if we’ve got hundreds of SSPs? If we want a full-mesh topology connecting every SSP to every other SSP directly, we’d have a rats nest of links!

So to keep things clean and scalable, we’ve got Signalling Transfer Points (STPs).

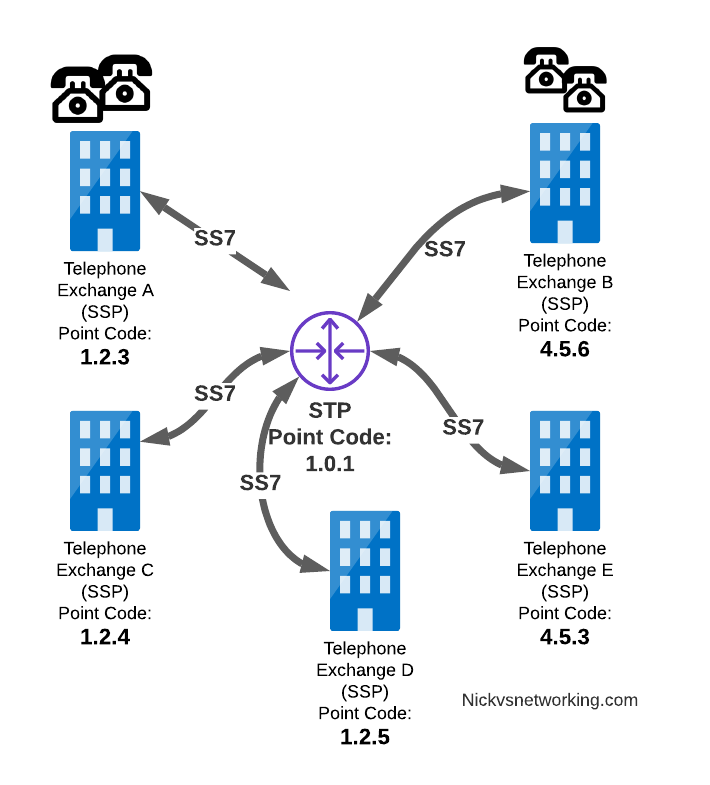

STPs can be thought of like Routers but in an SS7 network.

When our SSP generates an SS7 message, it’s typically handed to an STP which looks at the Destination Point Code, it’s own routing table and routes it off to where it needs to go.

This means every SSP doesn’t require a connection to every other SSP. Instead by using STPs we can cut down on the complexity of our network.

When Telephone Exchange A wants to send a message over SS7 to Telephone Exchange B, the MTP header would look the same, but the routing table on Telephone Exchange A would be setup to send the requests out the link towards the STP.

MTP3 Header: Origin Point Code: 1.2.3 Destination Point Code: 4.5.6

Linksets

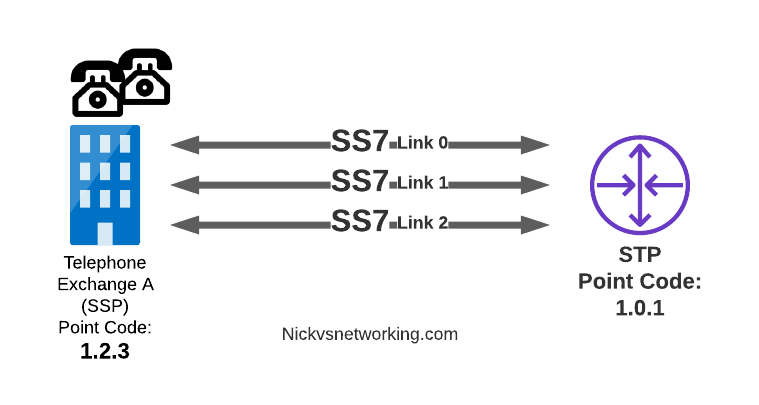

Between SS7 Nodes we have Linksets. Think of Linksets as like LACP or Etherchannel, but for SS7.

You want to have multiple links on every connection, for sharing out the load or for redundancy, and a Linkset is a group of connections from one SS7 node to another, that are logically treated as one link.

Each of the links in a Linkset is identified by a number, and specified in in the MTP3 header’s “Signaling Link Selector” field, so we know what link each message used.

MTP3 Header: Origin Point Code: 1.2.3 Destination Point Code: 4.5.6 Signaling Link Selector: 2

Service Control Point (SCP)

Somewhere between a Rolodex an relational database, is the Service Control Point (SCP).

For an exchange (SSP) to route a call to another exchange, it has to know the point code of the destination Exchange to send the call to.

When fixed line networks were first deployed this was fairly straight forward, each exchange had a list of telephone number prefixes and the point code that served each prefix, simple.

But then services like number porting came along when a number could be moved anywhere.

Then 1800/0800 numbers where a number had to be translated back to a standard phone number entered the picture.

To deal with this we need a database, somewhere an SSP can go to query some information in a database and get a response back.

This is where we use the Service Control Point (SCP).

Keep in mind that SS7 long predates APIs to easily lookup data from a service, so there was no RESTful option available in the 1980s.

When a caller on a local exchange calls a toll free (1800 or 0800 number depending on where you are) number, the exchange is setup with the Point Code of an SCP to query with the toll free number, and the SCP responds back with the local number to route the call to.

While SCPs are fading away in favor of technology like DNS/ENUM for Local Number Portability or Routing Databases, but they are still widely used in some networks.

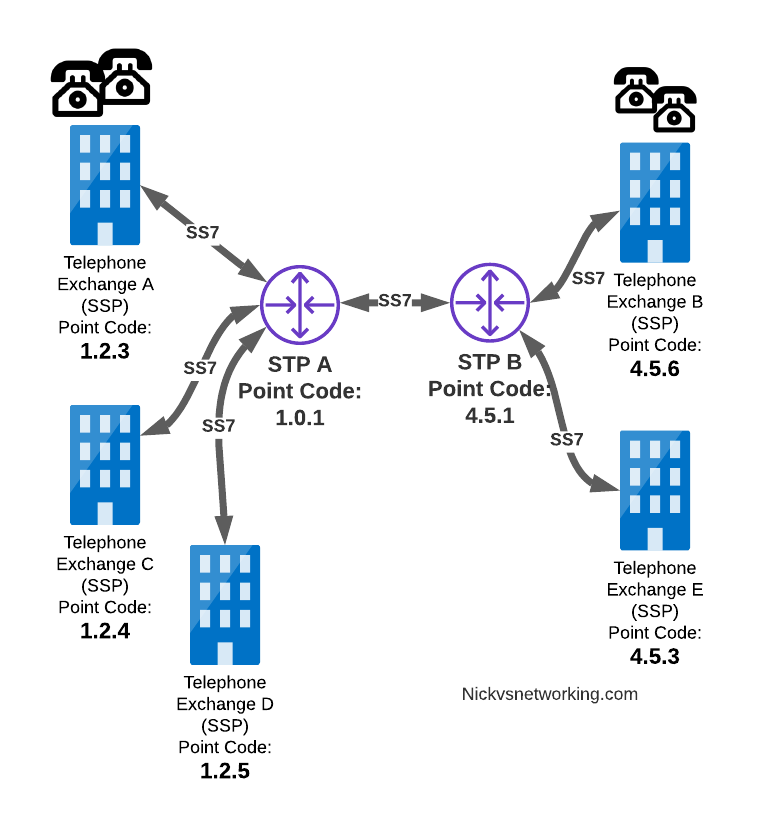

Getting to know the Signalling Transfer Point (STP)

As we saw earlier, instead of a one-to-one connection between each SS7 device to every other SS7 device, Signaling Transfer Points (STP) are used, which act like routers for our SS7 traffic.

The STP has an internal routing table made up of the Point Codes it has connections to and some logic to know how to get to each of them.

Like a router, STPs don’t really create SS7 traffic, or consume traffic, they just receive SS7 messages and route them on towards their destination.

Ok, they do create some traffic for checking links are up, etc, but like a router, their main job is getting traffic where it needs to go.

When an STP receives an SS7 message, the STP looks at the MTP3 header. Specifically the Destination Point Code, and finds if it has a path to that Point Code. If it has a route, it forwards the SS7 message on to the next hop.

Like a router, an STP doesn’t really concern itself with anything higher than the MTP3 layer – As point codes are set in the MTP3 layer that’s the only layer the STP looks at and the upper layers aren’t really “any of its business”.

STPs don’t require a direct connection (Linkset) from the Originating Point Code straight to the Destination Point Code. Just like every IP router doesn’t need a direct connection to ever other network.

By setting up a routing table of Point Codes and Linksets as the “next-hop”, we can reach Destination Point Codes we don’t have a direct Linkset to by routing between STPs to reach the final Destination Point Code.

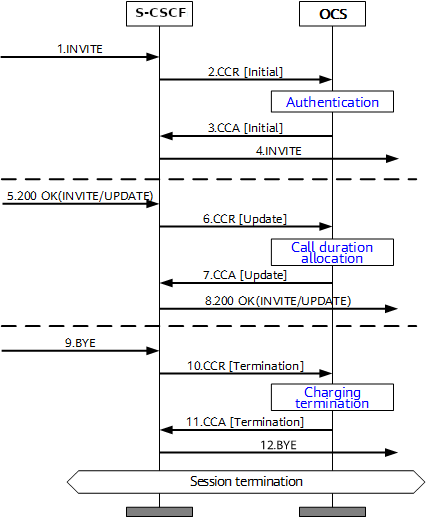

Let’s work through an example:

And let’s look at the routing table setup on STP-A:

STP A Routing Table: 1.2.3 - Directly attached (Telephone Exchange A) 1.2.4 - Directly attached (Telephone Exchange C) 1.2.5 - Directly attached (Telephone Exchange D) 4.5.1 - Directly attached (STP-B) 4.5.3 - Via STP-B 4.5.6 - Via STP-B

So what happens when Telephone Exchange A (Point Code 1.2.3) wants to send a message to Telephone Exchange E (Point Code 4.5.3)?

Firstly Telephone Exchange A puts it’s message on an MTP3 payload, and the MTP3 header will look something like this:

MTP3 Header: Origin Point Code: 1.2.3 Destination Point Code: 4.5.3 Signaling Link Selector: 1

Telephone Exchange A sends the SS7 message to STP A, which looks at the MTP3 header’s Destination Point Code (4.5.3), and then in it’s routing table for a route to the destination point. We can see from our example routing table that STP A has a route to Destination Point Code 4.5.3 via STP-B, so sends it onto STP-B.

For STP-B it has a direct connection (linkset) to Telephone Exchange E (Point Code 4.5.3), so sends it straight on

Like IP, Point Codes have their own form of Variable-Length-Subnet-Routing which means each STP doesn’t need full routing info for every Destination Point Code, but instead can have routes based on part of the point code and a subnet mask.

But unlike IP, there is no BGP or OSPF on SS7 networks. Instead, all routes have to be manually specified.

For STP A to know it can get messages to destinations starting with 4.5.x via STP B, it needs to have this information manually added to it’s route table, and the same for the return routing.

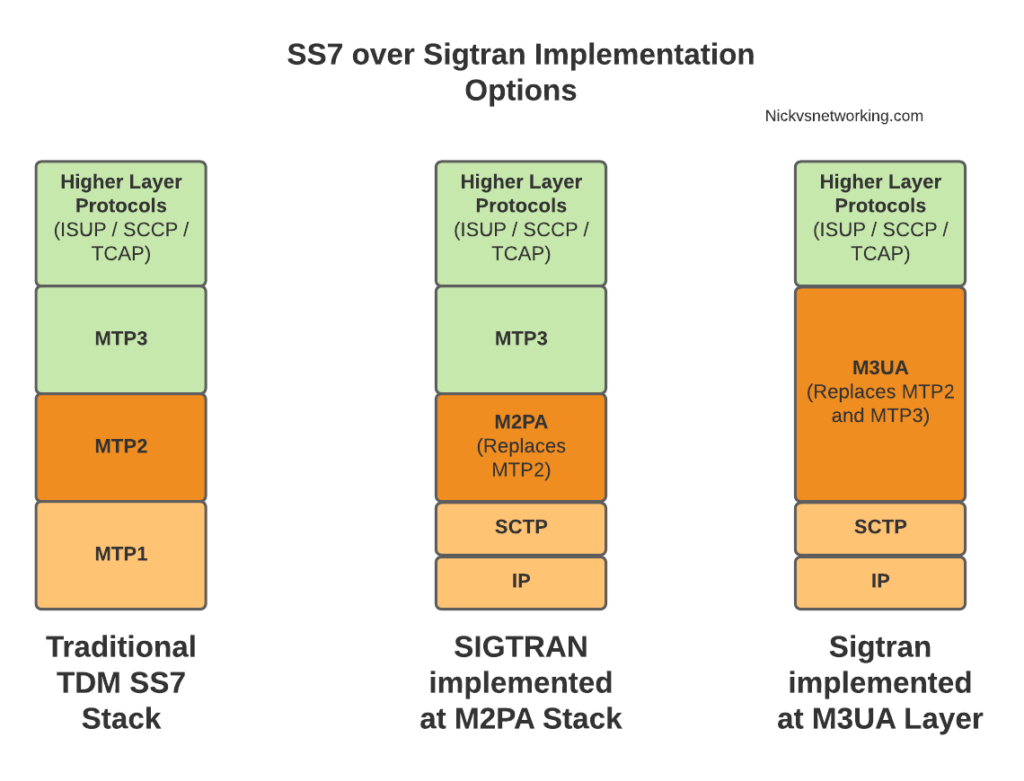

Sigtran & SS7 Over IP

As the world moved towards IP enabled everything, TDM based Sigtran Networks became increasingly expensive to maintain and operate, so a IETF taskforce called SIGTRAN (Signaling Transport) was created to look at ways to move SS7 traffic to IP.

When moving SS7 onto IP, the first layer of SS7 (MTP1) was dropped, as it primarily concerned the physical side of the network. MTP2 didn’t really fit onto an IP model, so a two options were introduced for transport of the MTP2 data, M2PA (Message Transfer Part 2 User Peer-to-Peer Adaptation Layer) and M2UA (MTP2 User Adaptation Layer) were introduced, which rides on top of SCTP.

This means if you wanted an MTP2 layer over IP, you could use M2UA or M2TP.

SCTP is neither TCP or UDP. I’ve touched upon SCTP on this blog before, it’s as if you took the best bits of TCP without the issues like head of line blocking and added multi-homing of connections.

So if you thought all the layers above MTP2 are just transferred, unchanged on top of our M2PA layer, that’s one way of doing it, however it’s not the only way of doing it.

There are quite a few ways to map SS7 onto IP Networks, which we’ll start to look into it more detail, but to keep it simple, for the next few posts we’ll be assuming that everything above MTP2/M2PA remain unchanged.

In the next post, we’ll get some actual SS7 traffic flowing!