On July 9, 1970 a $10 million dollar program to link Australia from East to West via Microwave was officially opened.

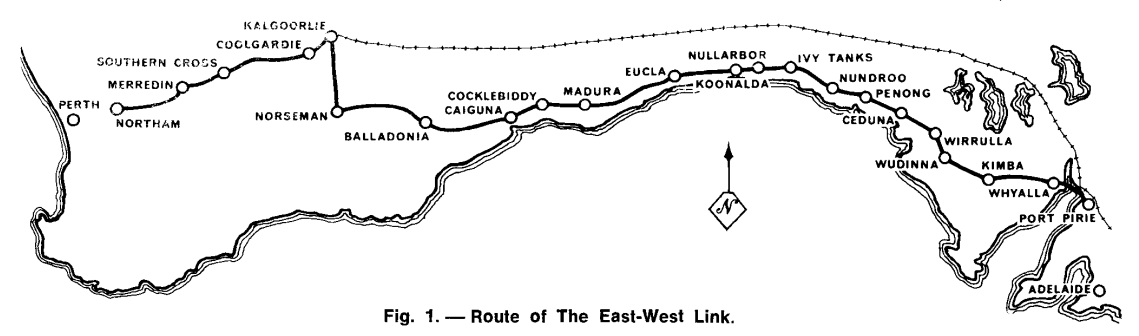

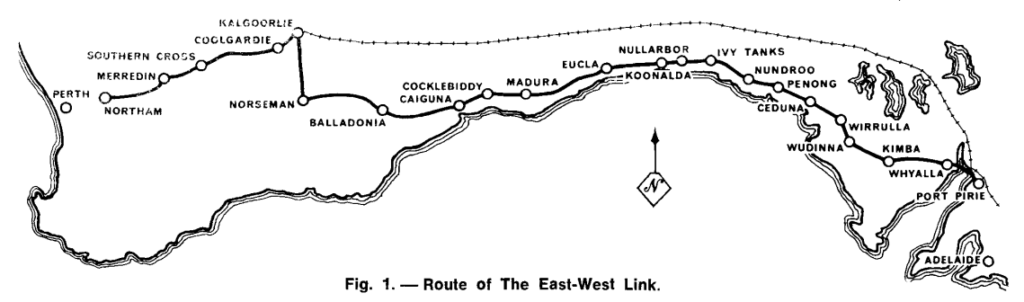

Spanning over 2,400 kilometres, it connected Northam (to the east of Perth) to Port Pirie (north of Adelaide) and thus connected the automated telephone networks of Australia’s Eastern States and Western States together, to enable users to dial each other and share video live, across the country, for the first time.

In 1877, long before road and rail lines, the first telegraph line – a single iron wire, was spanned across the Nullabor to link Australia’s Eastern states with Western Australia.

By 1930 an open-wire voice link had been established between the two sides of the continent.

This was open-wire circuit was upgraded a rebuilt several times, to finally top out at 140 channels, but by the 1960s Australian Post Office (APO) engineers knew a higher bandwidth (broadband carrier) system was required if ever Standard Trunk Dialling (STD) was to be implemented so someone in Perth could dial someone in Sydney without going via an operator.

A few years earlier Melbourne and Sydney were linked via a 600 kilometre long coaxial cable route, so API engineers spent months in the Nullarbor desert surveying the soil conditions and came to the conclusion that a coaxial cable (like the recently opened Melbourne to Sydney Coaxial cable) was possible, but would be very difficult to achieve.

Instead, in 1966, Alan Hume, the Postmaster-General, announced that the decision had been made to construct a network of Microwave relay stations to span from South Australia to Western Australia.

In the 1930s microwave communications had spanned the English channel, by 1951 AT&T’s Long Lines microwave network had opened, spanning the continental United States. So by the 1960’s Microwave transmission networks were commonplace throughout Europe and the US and was thought to be fairly well understood.

But soon APO engineers soon realised that the unique terrain of the desert and the weather conditions of the Nullabor, had significant impacts on the transmission of Radio Waves. Again Research Labs staff went back to spend months in the desert measuring signal strength between test sites to better understand how the harsh desert environment would impact the transmission in order to overcome these impediments.

The length of the link was one of the longest ever attempted, longer than the distance from London to Moscow,

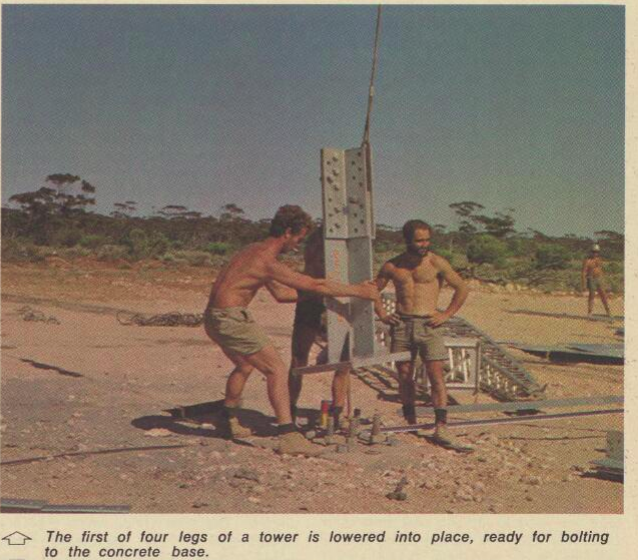

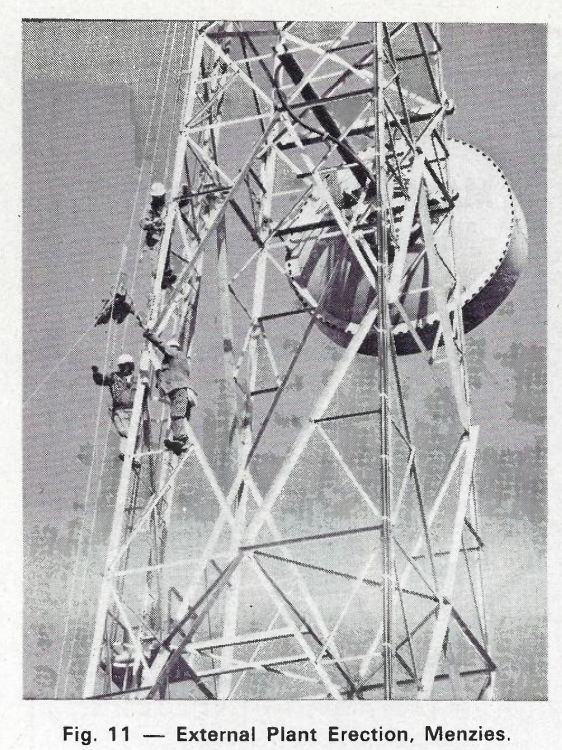

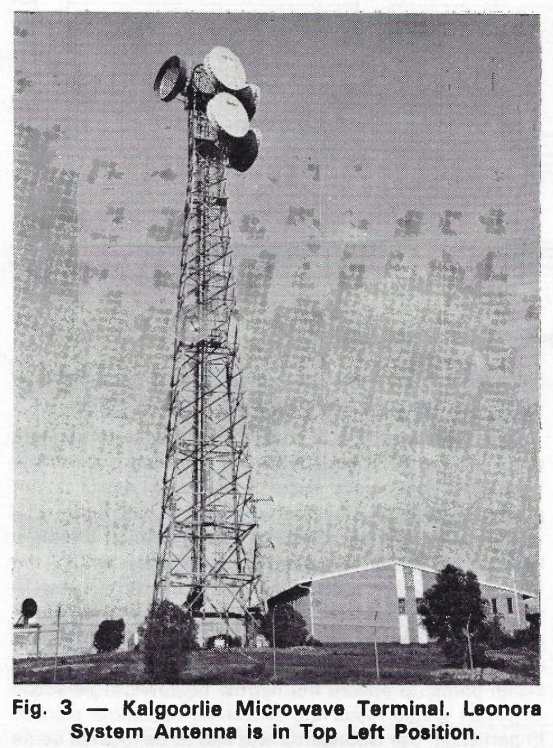

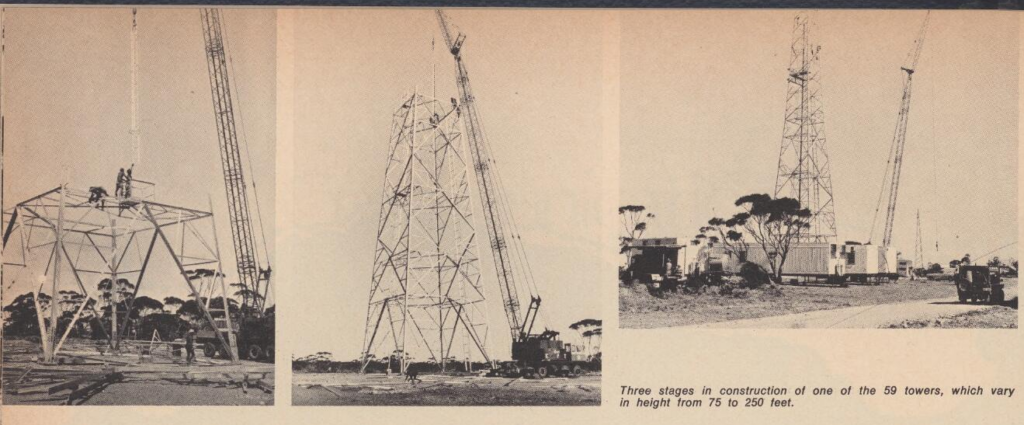

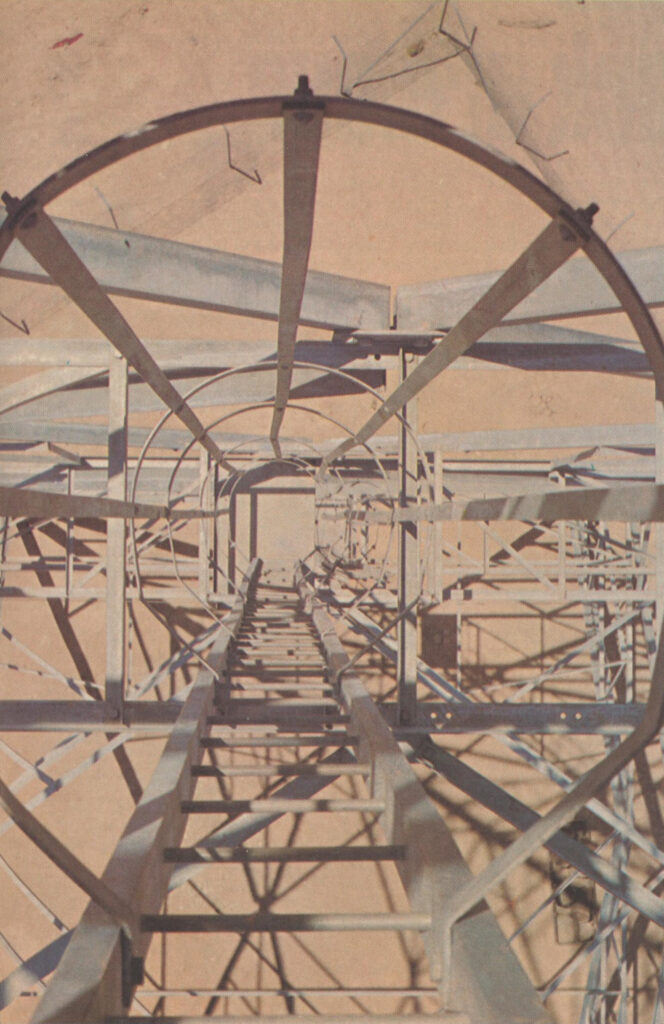

In the end it was decided that 59 towers with heights from 22 meters to 76 meters were to be built, topped off with 3.6m tall microwave dishes for relaying the messages between towers.

The towers themselves were to be built in a zig-zag pattern, to prevent overshooting microwave signals from interfering with signals for the next station in the chain.

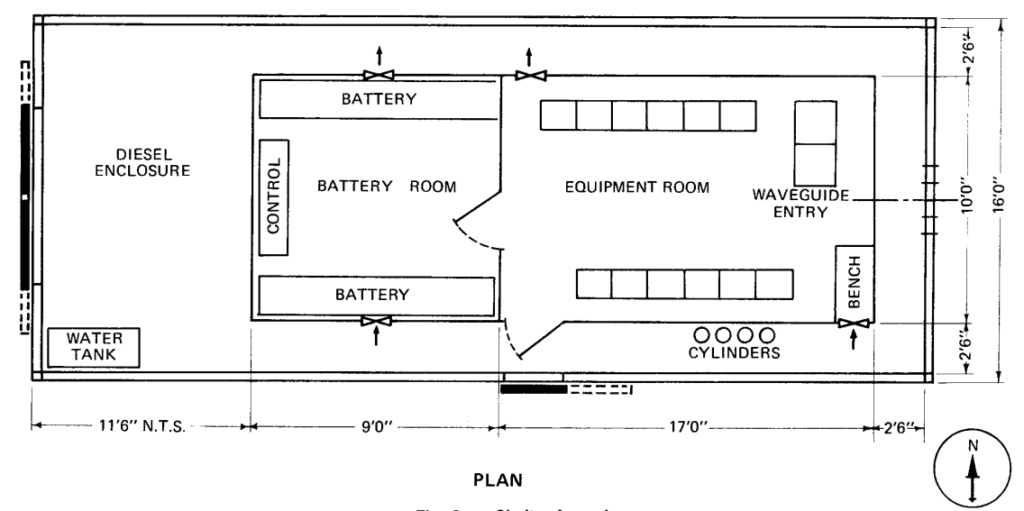

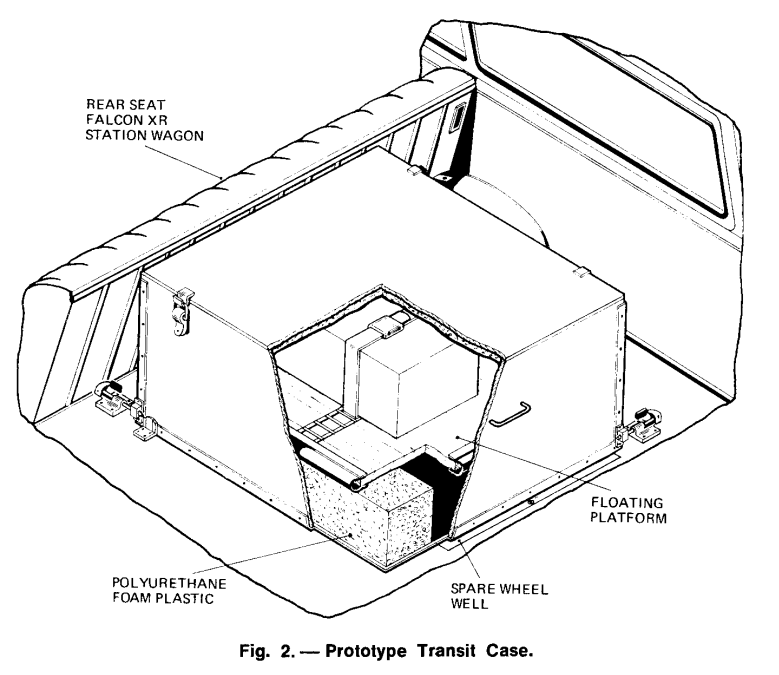

Due to the remote nature of the repeater sites, for 43 of the 59 repeater sites had to be fully self sufficient in terms of power.

Initial planning saw the power requirements of the repeater sites to be limited to 500 watts, APO engineers looked at the available wind patterns and determined that combined with batteries, wind generators could keep these sites online year round, without the need for additional power sources. Unfortunately this 500 watt power consumption target quickly tripled, and diesel generators were added to make up any shortfall on calm days.

The addition of the Diesel gensets did not in any way reduce the need to conserve power – the more Diesel consumed, the more trips across the desert to refuel the diesel generators would be required, so the constant need to keep power to a minimum was one of the key restraints in the project.

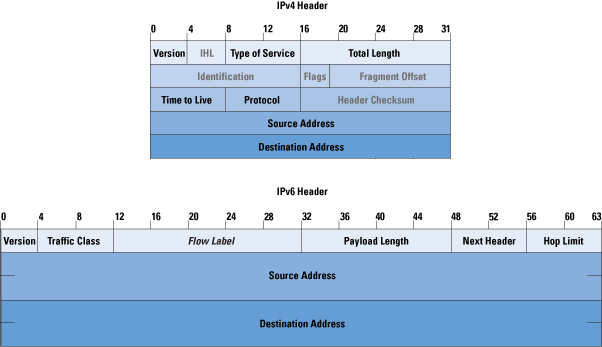

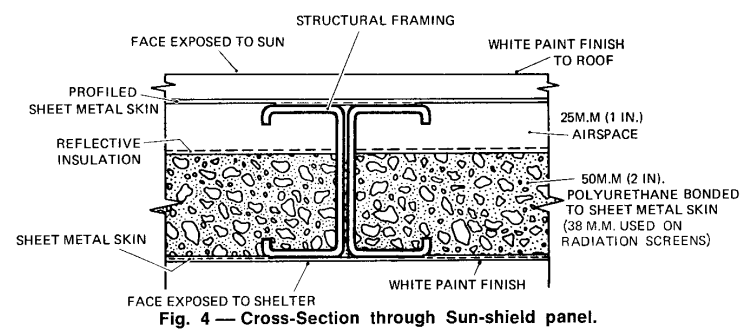

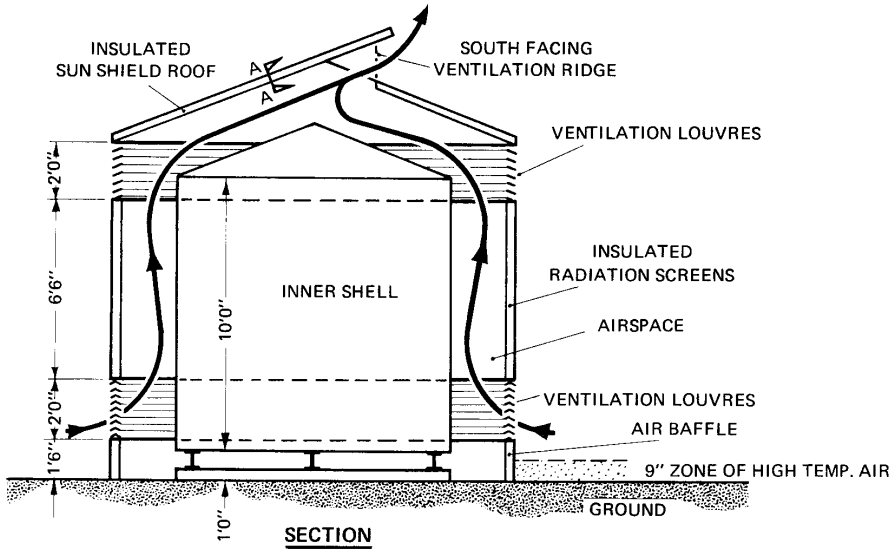

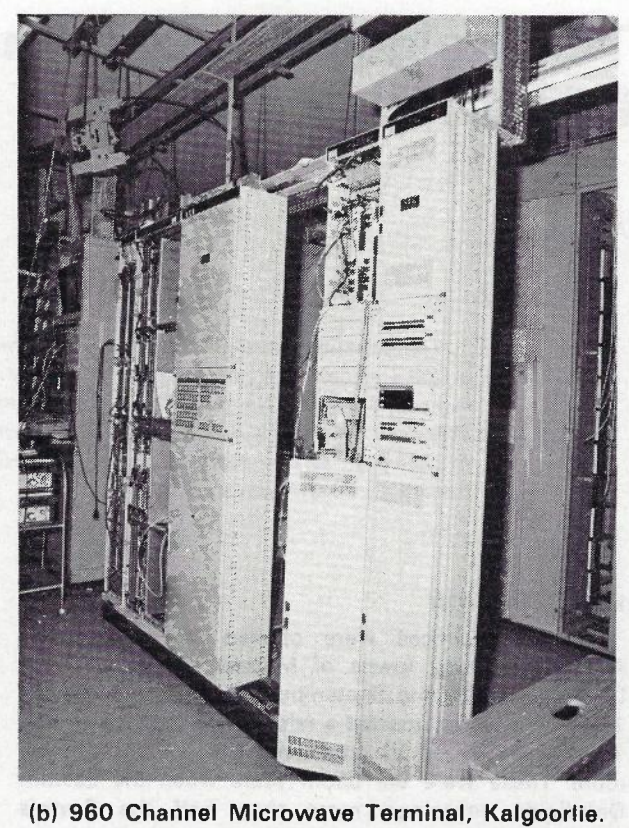

Active cooling systems (Like Air Conditioning) were out of the question due to being too power hungry. APO engineers knew that the more efficient equipment they could use, the less heat they would produce, and the more efficient the system would be, so solid state (transistorised devices) were selected for the 2Ghz transmission equipment, instead of valves which would have been more power-hungry and produced more heat.

The reduced power requirement of the fully transistorized radio equipment meant that wind-supplied driven generators could provide satisfactory amounts of power provided that the wind characteristics of the site were suitable.

THE TELECOMMUNICATION JOURNAL OF AUSTRALIA / Volume 21 / Issue 21 / February 1971

So forced to use passive cooling methods, the engineers on the project designed the repeater huts to cleverly utilize ventilation and the orientation of the huts to keep them as cool as possible.

Construction was rough, but in just under 2 years the teams had constructed all 59 towers and the associated equipment huts to span the desert.

When the system first opened for service in July 1970, live TV programs could be simulcast on both sides of the country, for the first time, and someone in Perth could pick up the phone and call someone in Melbourne directly (previously this would have gone through an operator).

The system offered 1+1 redundancy, and capacity for 600 circuits, split across up to 6 radio bearers, and a bearer could be dedicated at times to support TV transmissions, carried on 5 watt (2 watt when modulated) carriers, operating at 1.9 to 2.3Ghz.

By linking the two sides of Australia, Telecom opened up the ability to have a single time source distributed across the country, the station in Lyndhurst in Victoria, created the 100 “microseconds” signal generated by a VNG, that was carrier across the link.

Unlike AT&T’s Long Lines network, which lasted until after MCI, deregulation and the breakup off the Bell System, the East-West link didn’t last all that long.

By 1981, Telecom Australia (No longer APO) had installed their first experimental optic fibre cable between Clayton and Springvale, and fibre quickly became the preferred method for broadband carrier circuits between exchanges.

By 1987, Melbourne and Sydney were linked by fibre, and the benefits of fibre were starting to be seen more broadly, and by 1989, just under 20 years since the original East-West Microwave system opened, Telecom Australia completed a 2373 kilometre long / 14 fibre cable from Perth to Adelaide, and Optus followed in 1993.

This effectively made the microwave system redundant. Fibre provided a higher bandwidth, more reliable service, that was far cheaper to operate due to decreased power requirements. And so piece by piece microwave hops were replaced with fibre optic cables.

I’m not clear on which was the last link to be switched off (If you do know please leave a comment or drop me a message), but eventually at some point in the late 1980s or early 1990s, the system was decommissioned.

Many of the towers still stand today and carry microwave equipment on them, but it is a far cry from what was installed in the late 1960s.

References

East-west microwave link opening (Press Release)

Walkabout.Vol. 35 No. 6 (1 June 1969) – Communications Across the Nullabor

$8 Million Trans-continental link

ABC Goldfields-Esperance – Australia’s first live national television broadcast

APO – Newsletter ‘New East-West Trunks System’