This is part of a series of posts looking into SS7 and Sigtran networks. We cover some basic theory and then get into the weeds with GNS3 based labs where we will build real SS7/Sigtran based networks and use them to carry traffic.

So we’ve made it through the first two parts of this series talking about how it all works, but now dear reader, we build an SS7 Lab!

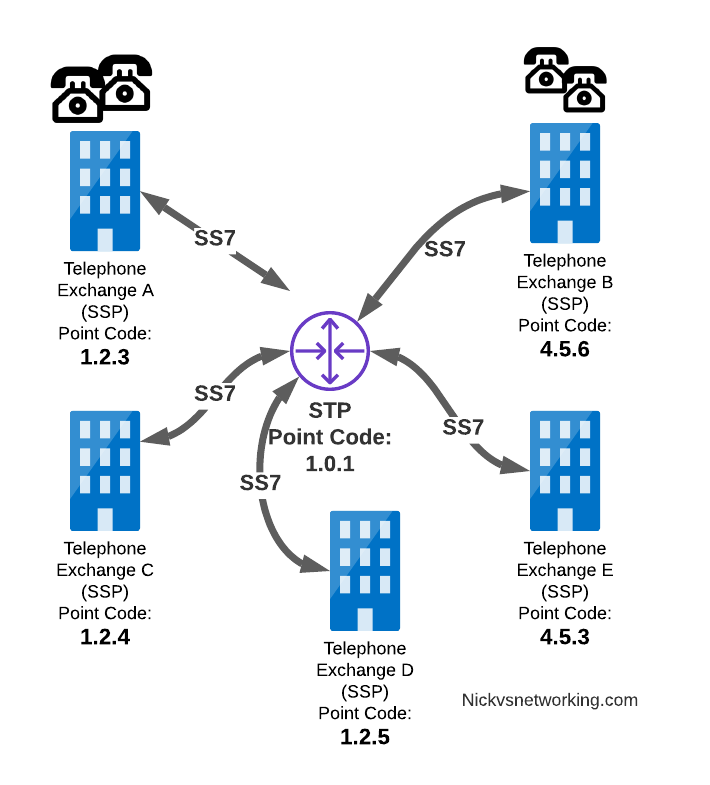

At one point, and SS7 Signaling Transfer Point would be made up of at least 3 full size racks, and cost $5M USD.

We can run a dozen of them inside GNS3!

This post won’t cover usage of GNS3 itself, there’s plenty of good documentation on using GNS3 if you need to get acquainted with it before we start.

Cisco’s “IP Transfer Point” (ITP) software adds SS7 STP functionality to some models of Cisco Router, like the 2651XM and C7200 series hardware.

Luckily for us, these hardware platforms can be emulated in GNS3, so that’s how we’ll be setting up our instances of Cisco’s ITP product to use as STPs in our network.

For the rest of this post series, I’ll refer to Cisco’s IP Transfer Point as the “Cisco STP”.

Not open source you say! Osmocom have OsmoSTP, which we’ll introduce in a future post, and elaborate on why later…

From inside GNS3, we’ll create a new template as per the Gif below.

You will need a copy of the software image to load in. If you’ve got software entitlements you should be able to download it, the filename of the image I’m using for the 7200 series is c7200-itpk9-mz.124-15.SW.bin and if you go searching, you should find it.

Now we can start building networks with our Cisco STPs!

What we’re going to achieve

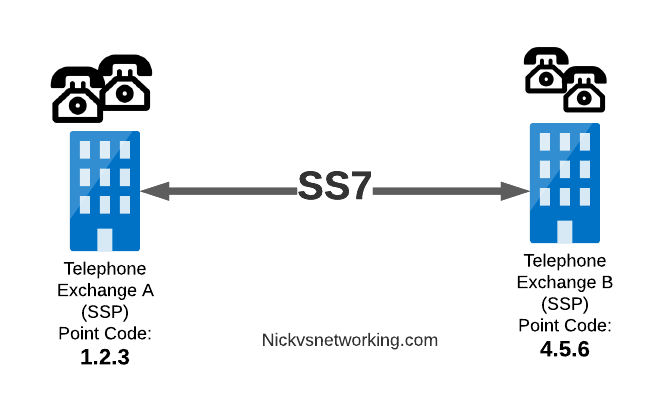

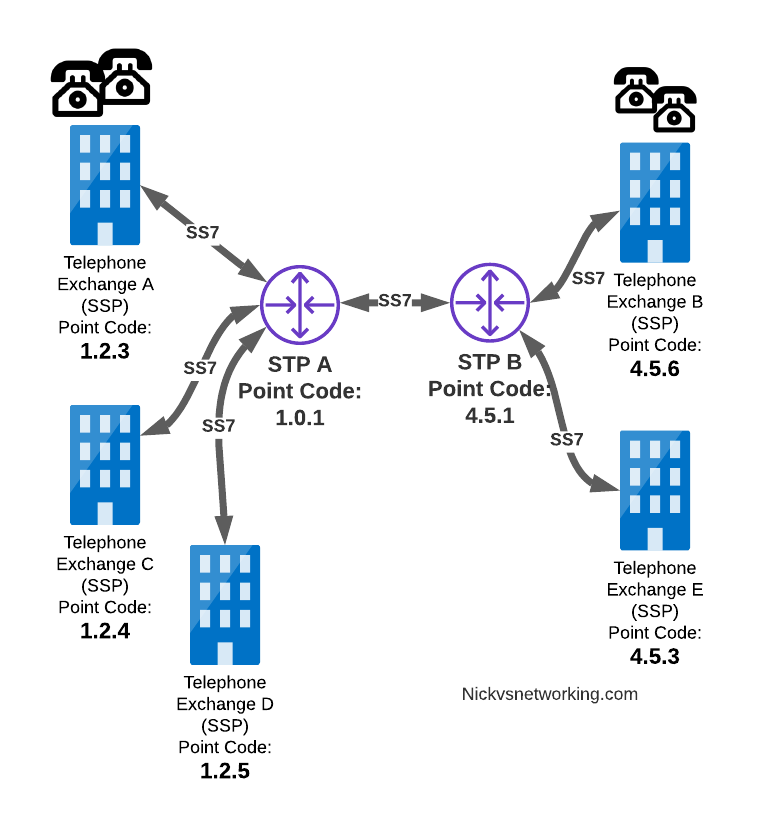

In this lab we’re going to introduce the basics of setting up STPs using Sigtran (SS7 over IP).

If you follow along, by the end of this post you should have two STPs talking Sigtran based SS7 to each other, and be able to see the SS7 packets in Wireshark.

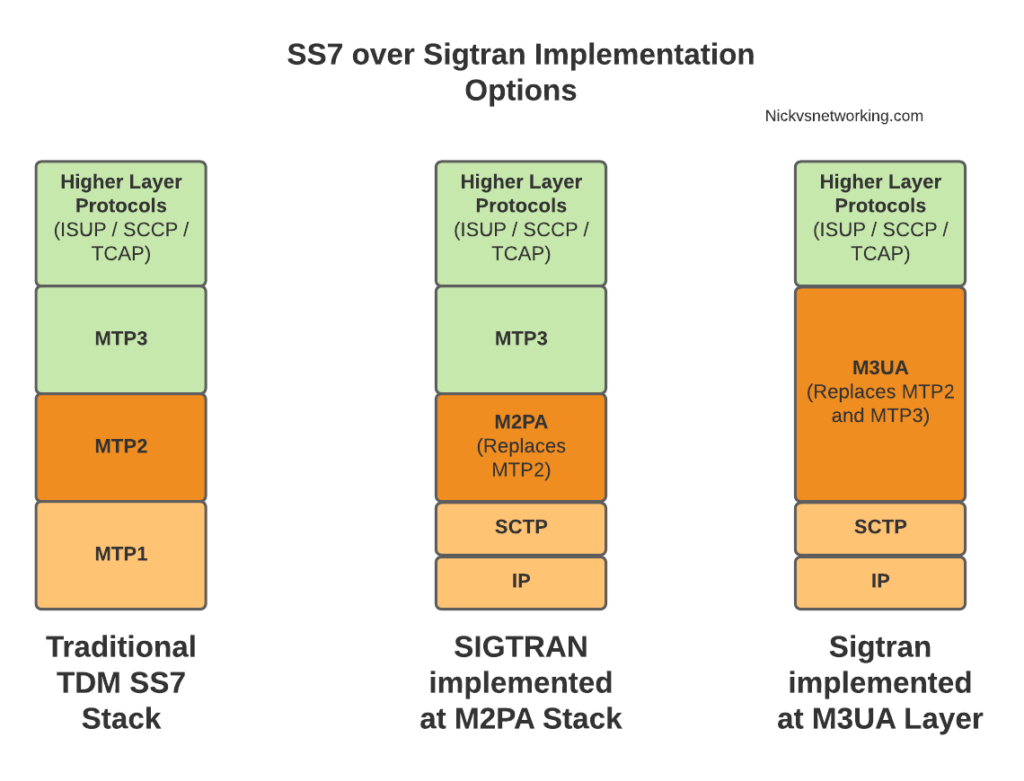

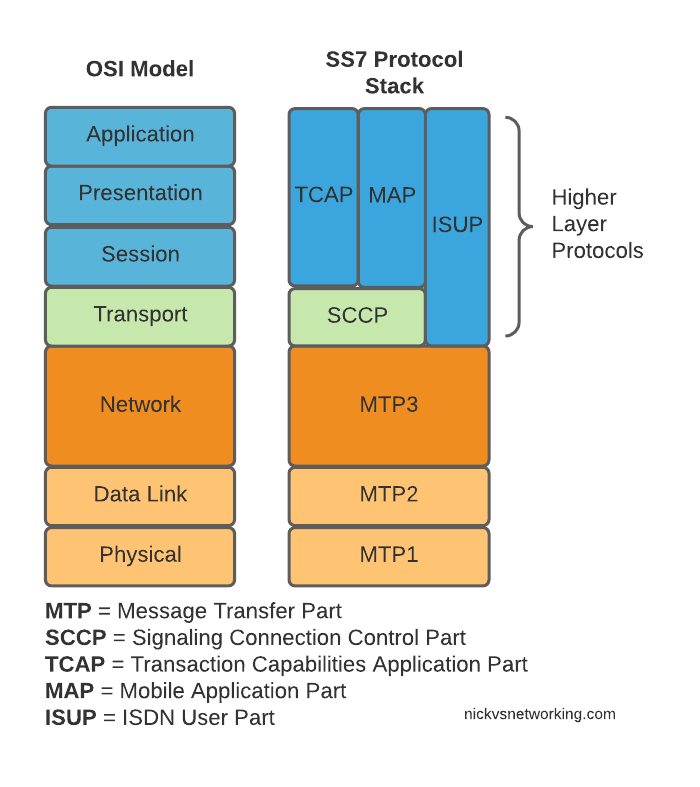

As we touched on in the last post, there’s a lot of different flavours and ways to implement SS7 over IP. For this post, we’re going to use M2PA (MTP2 Peer Adaptation Layer) to carry the MTP2 signaling, while MTP3 and higher will look the same as if it were on a TDM link. In a future post we’ll better detail the options here, the strengths and weaknesses of each method of transporting SS7 over IP, but that’s future us’ problem.

IP Connectivity

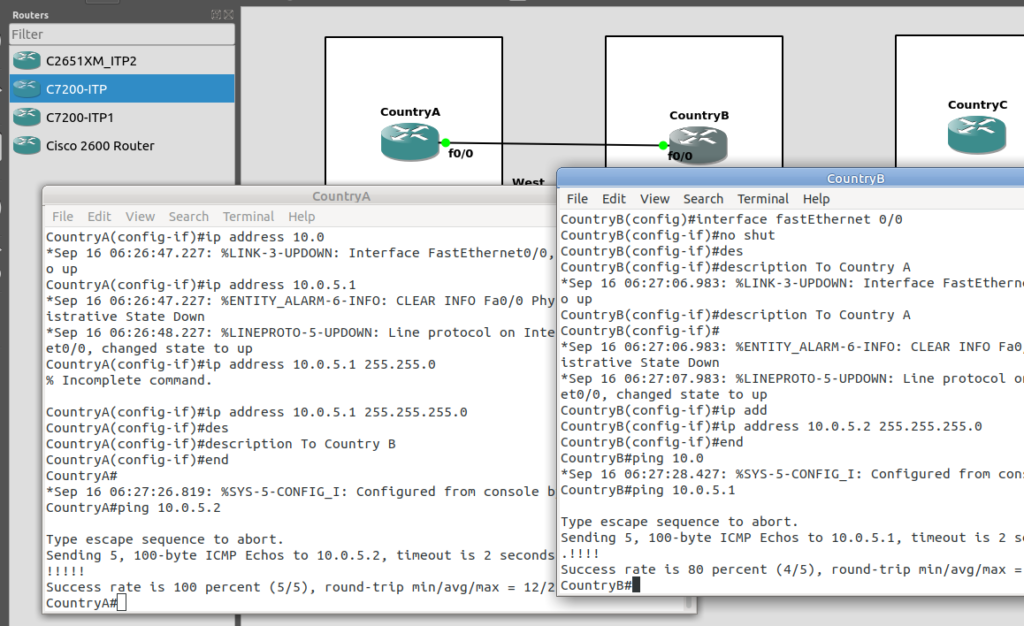

As we don’t have any TDM links, we’re going to do everything on IP, this means we have to setup the IP layer, before we can add any SS7/Sigtran stuff on top, so we’re going to need to get basic IP connectivity going between our Cisco STPs.

So for this we’ll need to set an IP Address on an interface, unshut it, link the two STPs. Once we’ve confirmed that we’ve got IP connectivity running between the two, we can get started on the Sigtran / SS7 side of things.

Let’s face it, if you’re reading this, I’m going to bet that you are probably aware of how to configure a router interface.

I’ve put a simple template down in the background to make a little more sense, which I’ve attached here if you want to follow along with the same addressing, etc.

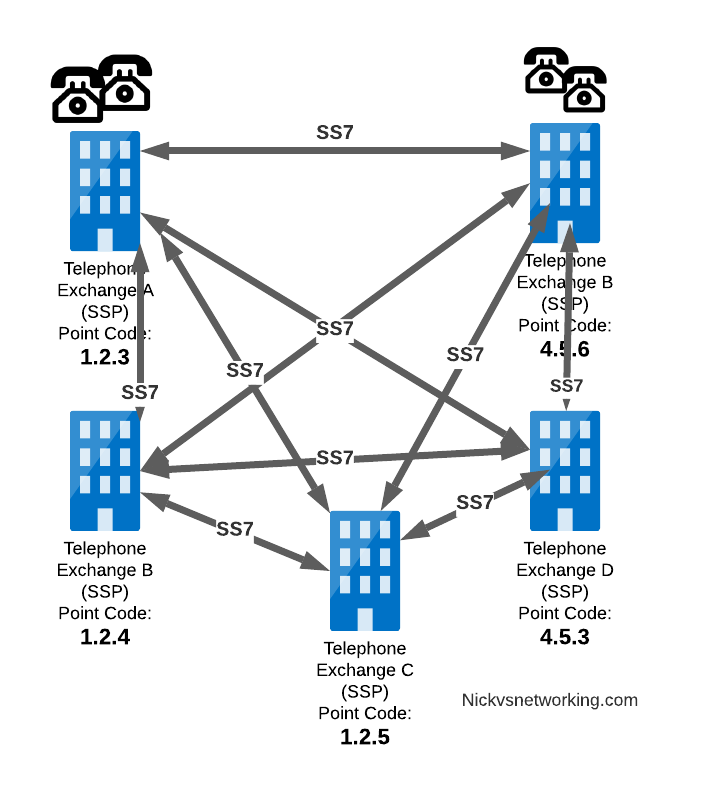

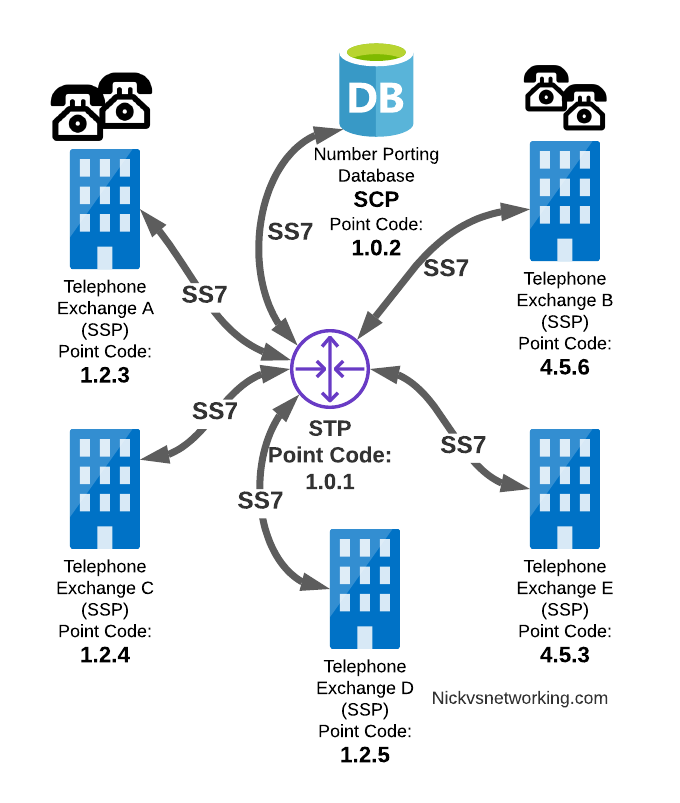

So we’ll configure all the routers in each country with an IP – we don’t need to configure IP routing. This means adjacent countries with a direct connection between them should be able to ping each other, but separated countries shouldn’t be able to.

So now we’ve got IP connectivity between two countries, let’s get Sigtran / SS7 setup!

First we’ll need to define the basics, from configure-terminal in each of the Cisco STPs. We’ll need to set the SS7 variant (We’ll use ITU variant as we’re simulating international links), the network-indicator (This is an International network, so we’ll use that) and the point code for this STP (From the background image).

CountryA(config)#cs7 variant itu

CountryA(config)#cs7 network-indicator international

CountryA(config)#cs7 point-code 1.2.3Repeat this step on Country A and Country B.

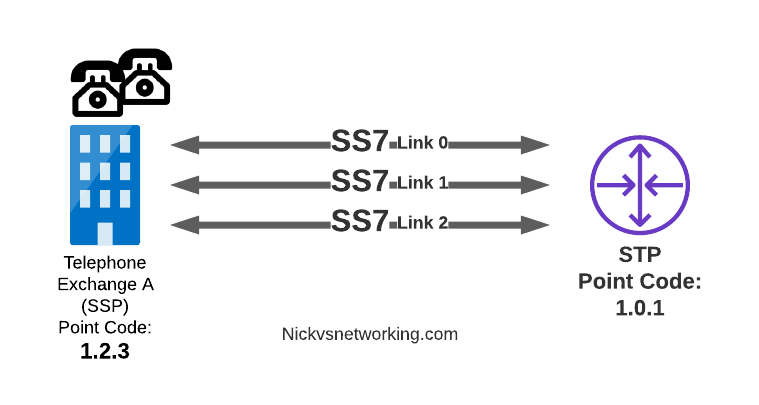

Next we’ll define a local peer on the STP. This is an instance of the Sigtran stack along with the port we’ll be listening on. Our remote peer will need to know this value to bring up the connection, the number specified is the port, and the IP is the IP it will bind on.

CountryA(config)#cs7 local-peer 1024

CountryA(config-cs7-lp)#local-ip 10.0.5.1

If we had multiple layer 3 IP Interfaces connecting Country A & Country B, we could list all the IP Addresses here for SCTP Multihoming.

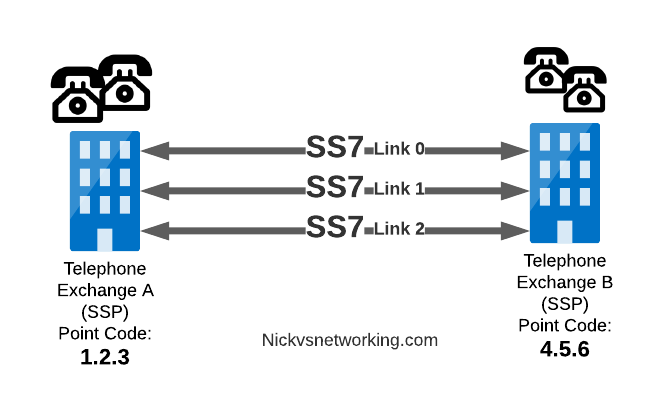

Lastly on Country A we’ll need to define our Linkset to connect to our peer.

CountryA(config)#cs7 linkset ToCountryB 4.5.6

CountryA(config-cs7-ls)#link 0 sctp 10.0.5.2 1024 1024Where the first 1024 is the local-peer port we configured earlier, and the second 1024 is the remote peer port we’re about to configure on Country B.

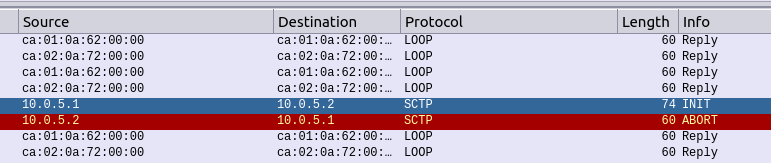

If we stop at this point and sniff the traffic from Country A to Country B, we’ll see SCTP INITs from Country A to Country B, as it tries to bring up the SCTP connection for our SS7 traffic, and the SCTP connection gets rejected by Country B.

This is of course, because we’ve only configured Country A at this stage, so let’s fix this by configuring Country B.

On CountryB, again we’ll set the basic parameters, our local-peer settings and the Linkset to bring up,

CountryB(config)#cs7 variant itu

CountryB(config)#cs7 network-indicator international

CountryB(config)#cs7 point-code 4.5.6

CountryB(config)#cs7 local-peer 1024

CountryB(config-cs7-lp)#local-ip 10.0.5.2

CountryB(config-cs7-lp)#exit

CountryB(config)#cs7 linkset ToCountryA 1.2.3

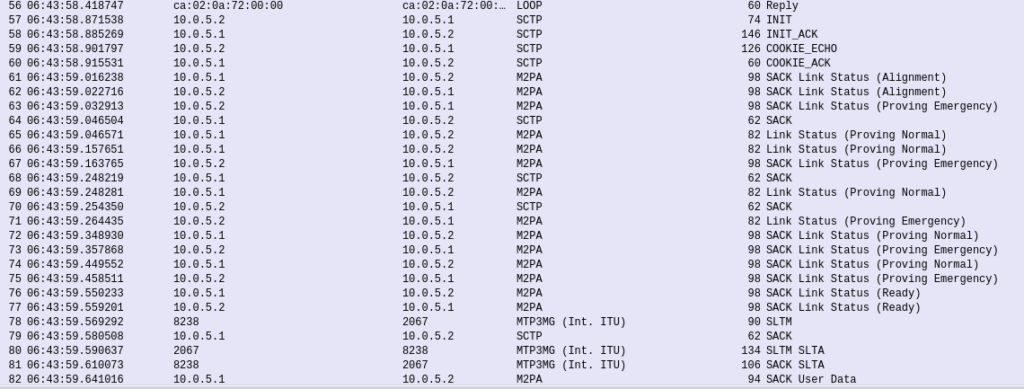

CountryB(config-cs7-ls)#link 0 sctp 10.0.5.1 1024 1024If you’re still sniffing the traffic between Country A and Country B, you should see our SS7 connection come up.

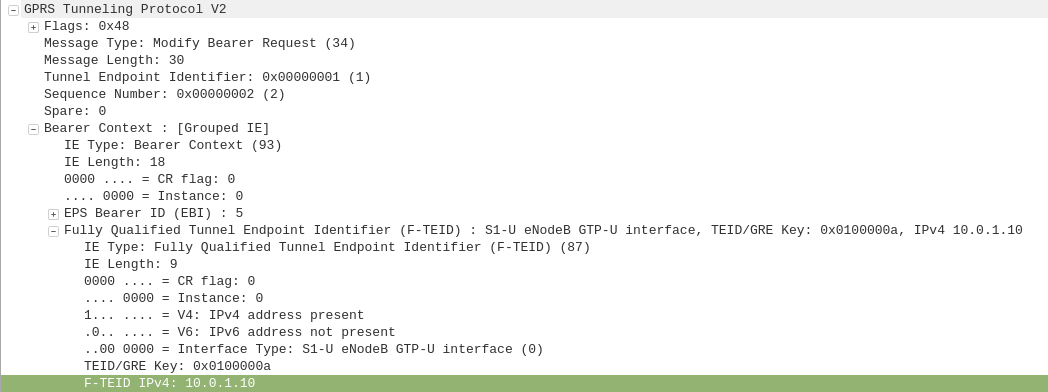

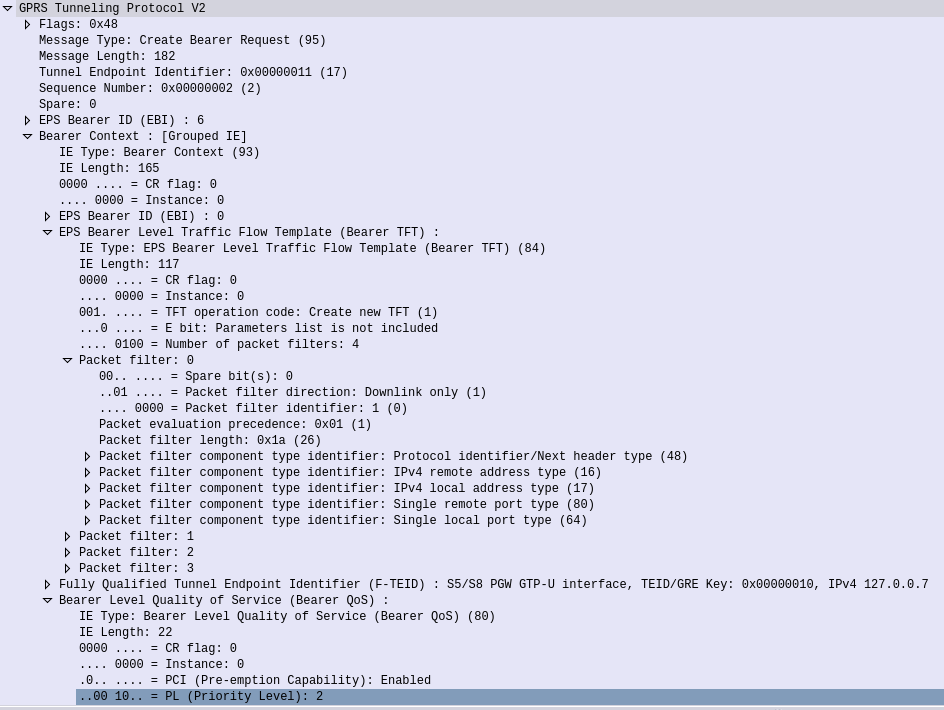

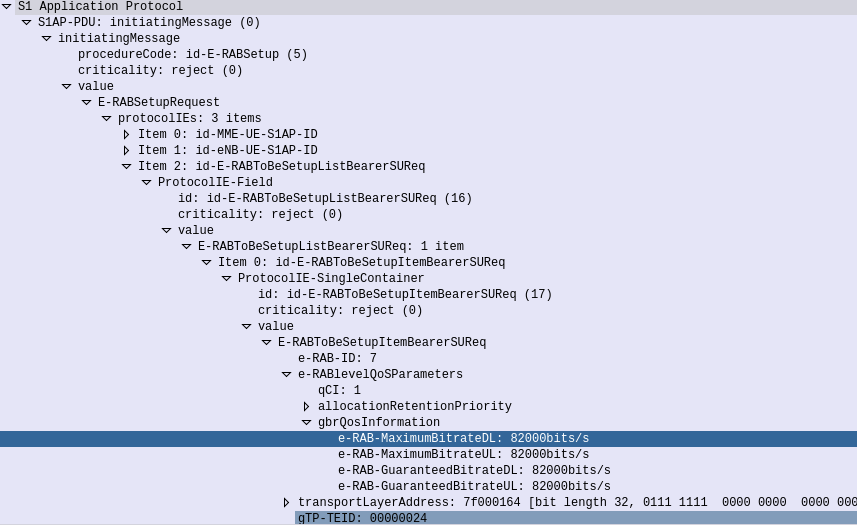

The conneciton will come up layer-by-layer, firstly you’ll see the transport layer (SCTP) bring up an SCTP association, then MTP2 Peer Adaptation Layer (M2PA) will negotiate up to confirm both ends are working, then finally you’ll see MTP3 messaging.

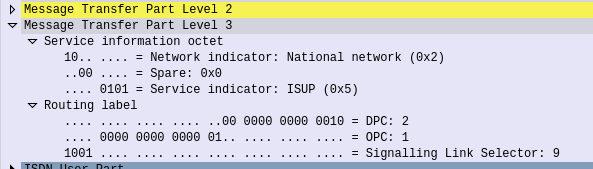

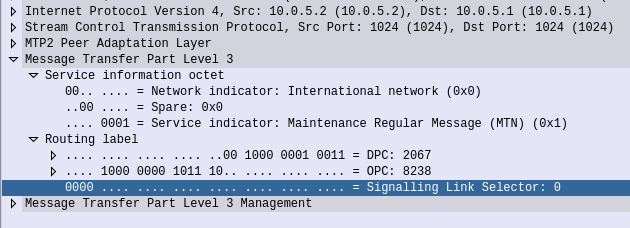

If we open up an MTP3 packet you can see our Originating and Destination Point Codes.

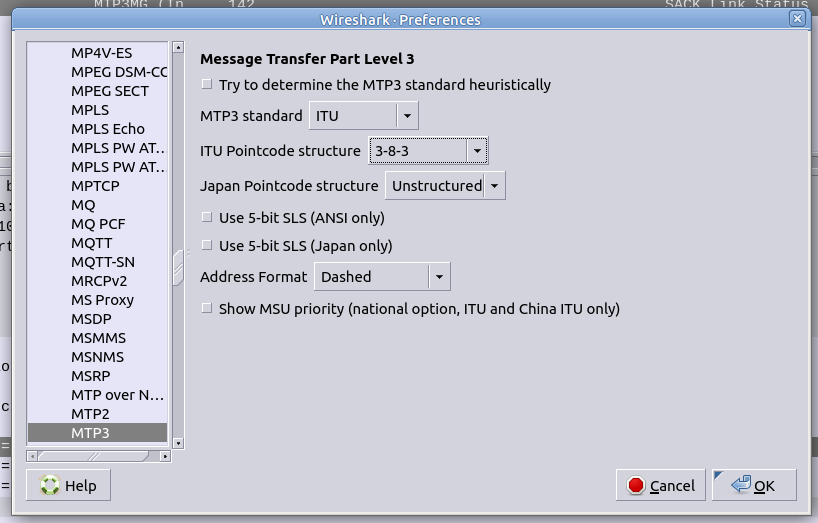

Notice in Wireshark the Point Codes don’t show up as 1-2-3, but rather 2067? That’s because they’re formatted as Decimal rather than 14 bit, this handy converter will translate them for you, or you can just change your preference in Wireshark’s decoders to use the matching ITU POint Code Structure.

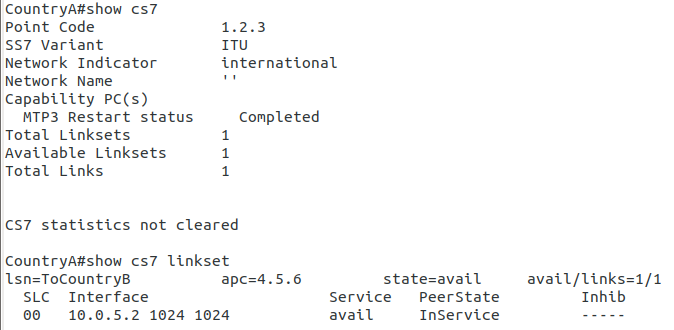

From the CLI on one of the two country STPs we can run some basic commands to view the status of all SS7 components and Linksets.

And there you have it! Basic SS7 connectivity!

There is so much more to learn, and so much more to do!

By bringing up the link we’ve barely scratched the surface here.

Some homework before the next post, link all the other countries shown together, with Country D having a link to Country C and Country B. That’s where we’ll start in the lab – Tip: You’ll find you’ll need to configure a new cs7 local-peer for each interface, as each has its own IP.