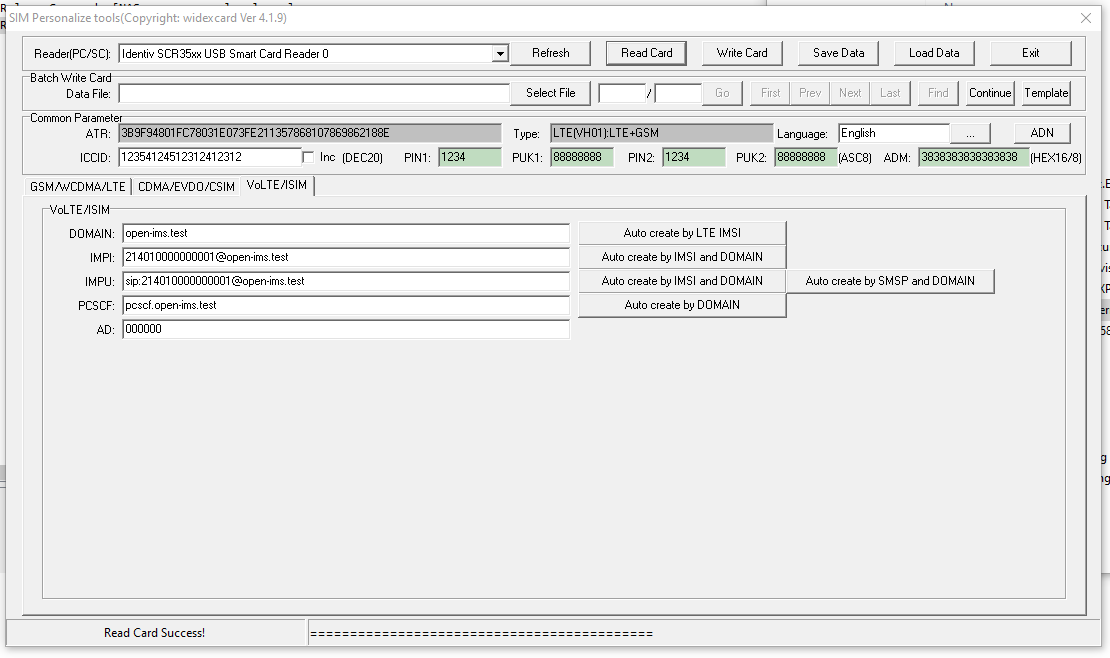

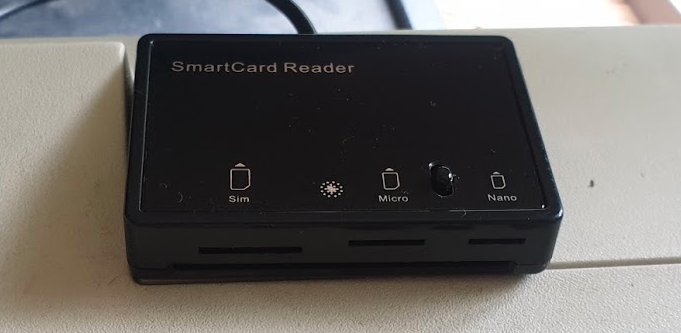

I’ve been working on private LTE recently, and one of the first barriers you’ll hit will be authentication.

LTE doesn’t allow you to just use any SIM to authenticate to the network, but instead relies on mutual authentication of the UE and the network, so the Network knows it’s talking to the right UE and the UE knows it’s talking to the right network.

So because of this, you have to have full control over the SIM and the network. So let’s take a bit of a dive into USIMs.

So it’s a SIM card right?

As a bit of background; the ever shrinking card we all know as a SIM is a “Universal integrated circuit card” – a microcontroller with it’s own OS that generally has the ability to run Java applets.

One of the Java applets on the card / microcontroller will be the software stack for a SIM, used in GSM networks to authenticate the subscriber.

For UMTS and LTE networks the card would have a USIM software stack allowing it to act as a USIM, the evolved version of the SIM.

Because it’s just software a single card can run both a USIM and SIM software stack, and most do.

As I’m building an LTE network we’ll just talk about the USIM side of things.

USIM’s role in Authentication

When you fire up your mobile handset the baseband module in it communicates with the USIM application on the card.

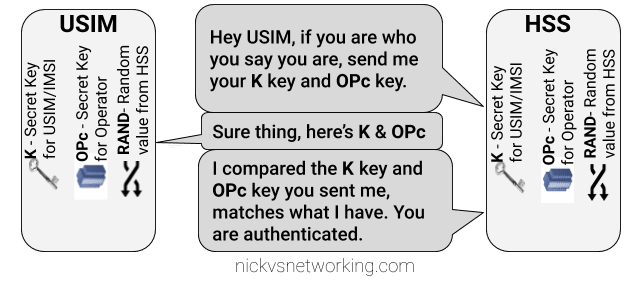

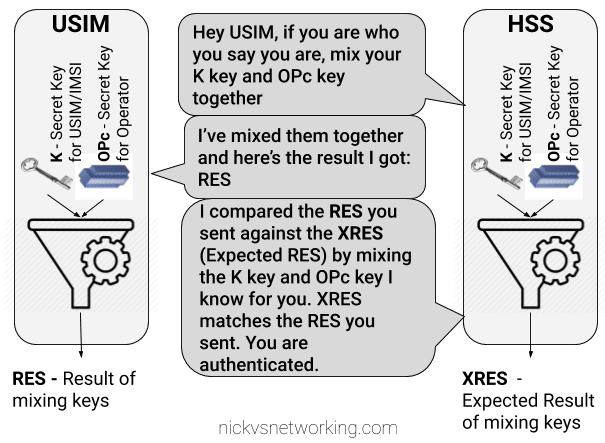

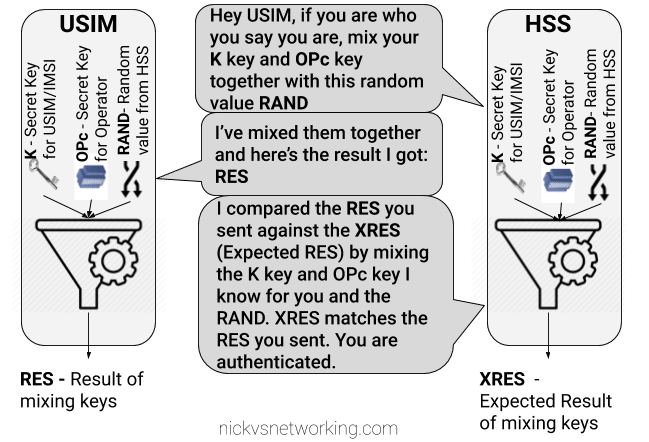

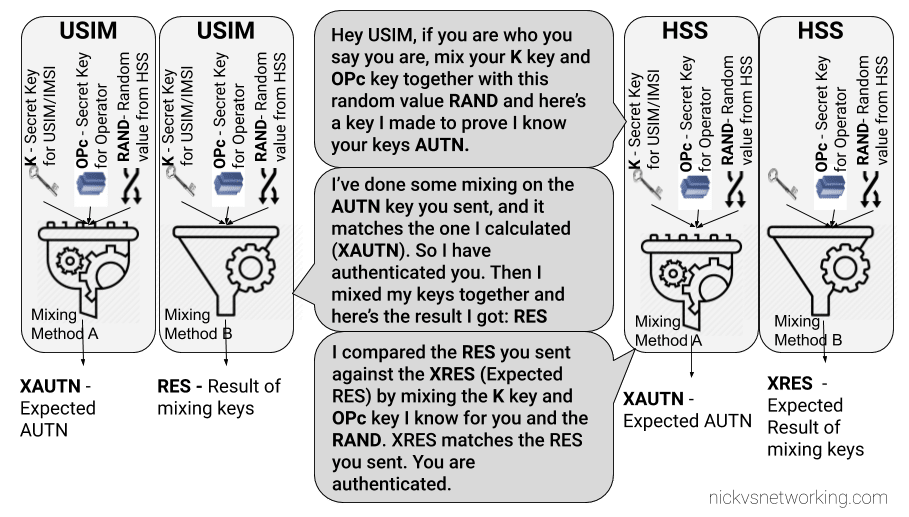

When it comes time to authenticate to the network, and authenticate the network itself, the baseband module sends the provided challenge information from the network to the USIM which does the crypto magic to generate responses to the authentication challenges issued by the network, and the USIM issues it’s own challenges to the network.

The Baseband module provides the ingredients, but the USIM uses it’s secret recipe / ingredients combo, known only to the USIM and HSS, to perform the authentication.

Because the card challenges the network it means we’ve got mutual authentication of the network.

This prevents anyone from setting up their own radio network from going all Lionel Ritche and saying “Hello, is it me you’re looking for” and having all the UEs attach to the malicious network. (Something that could be done on GSM).

It’s worth noting too that because the USIM handles all this the baseband module, and therefore the mobile handset itself, doesn’t know any of the secret sauce used to negotiate with the network. It just gets the challenge and forwards the ingredients down to the USIM which spits back the correct response to send, without sharing the magic recipe.

This also means operators can implement their own Crypto functions for f and g, so long as the HSS and the USIM know how to generate the RES and AUTN results, it’ll work.

What’s Inside?

Let’s take a look at the information that’s stored on your USIM:

All the GSM stuff for legacy SIM application

Generally USIMs also have the ability to operate as SIMs in a GSM network, after all it’s just a different software stack. We won’t touch on GSM SIMs here.

ICCID

Because a USIM is just an application running on a Universal Integrated Circuit Card, it’s got a ICCID or Universal Integrated Circuit Card ID. Generally this is the long barcode / string of numbers printed on the card itself.

The network generally doesn’t care about this value, but operators may use it for logistics like shipping out cards.

PIN & PUK

PINs and PUKs are codes to unlock the card. If you get the PIN wrong too many times you need the longer PUK to unlock it.

These fields can be written to (when authenticated to the card) but not read directly, only challenged. (You can try a PIN, but you can’t see what it’s set too).

As we mentioned before the terminal will ask the card if that’s correct, but the terminal doesn’t know the PIN either.

IMSI

Each subscriber has an IMSI, an International Mobile Subscriber Identity.

IMSIs are hierarchical, starting with 3 digit Mobile Country Code MCC, then the Mobile Network Code (MNC) (2/3 digits) and finally a Mobile Subscription Identification Number (MSIN), a unique number allocated by the operator to the subscribers in their network.

This means although two subscribers could theoretically have the same MSIN they wouldn’t share the same MNC and MCC so the ISMI would still be unique.

The IMSI never changes, unless the subscriber changes operators when they’ll be issued a new USIM card by the new operator, with a different IMSI (differing MNC).

The MSIN isn’t the same as the phone number / MSISDN Number, but an IMSI generally has a MSISDN associated with it by the network. This allows you to port / change MSISDN numbers without changing the USIM/SIM.

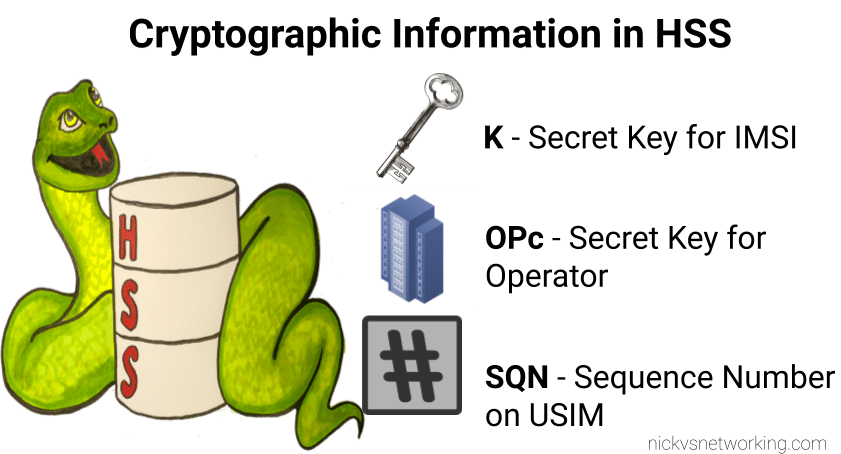

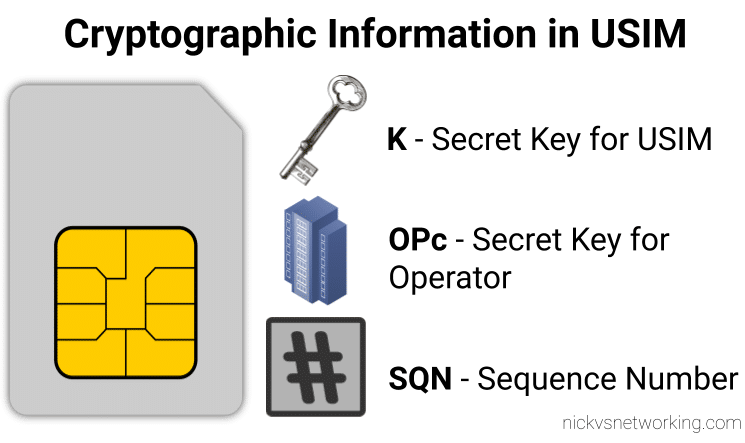

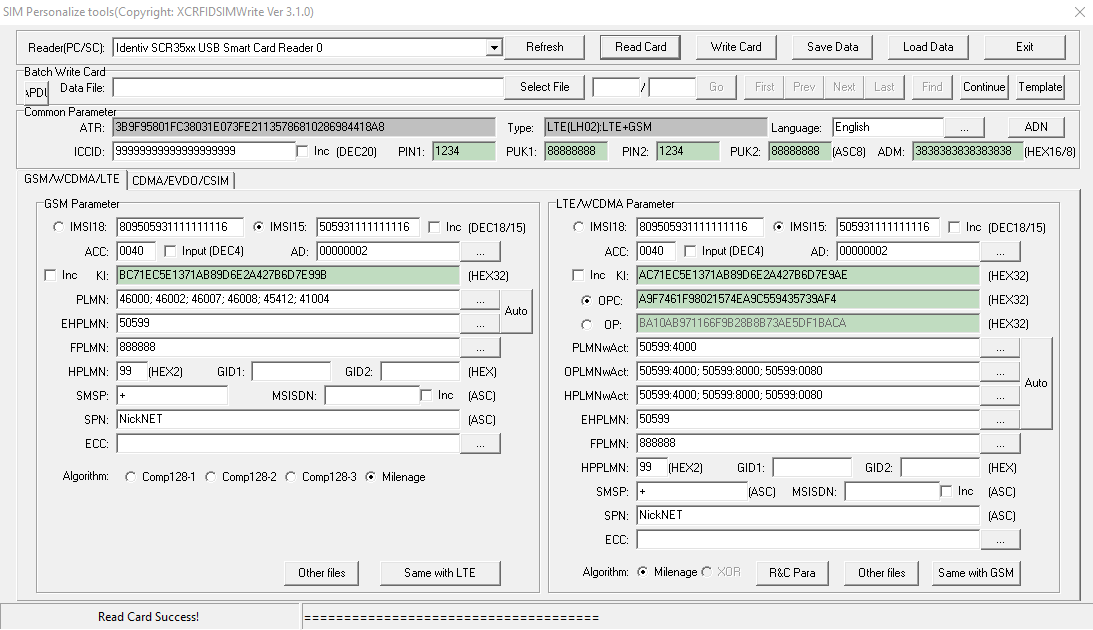

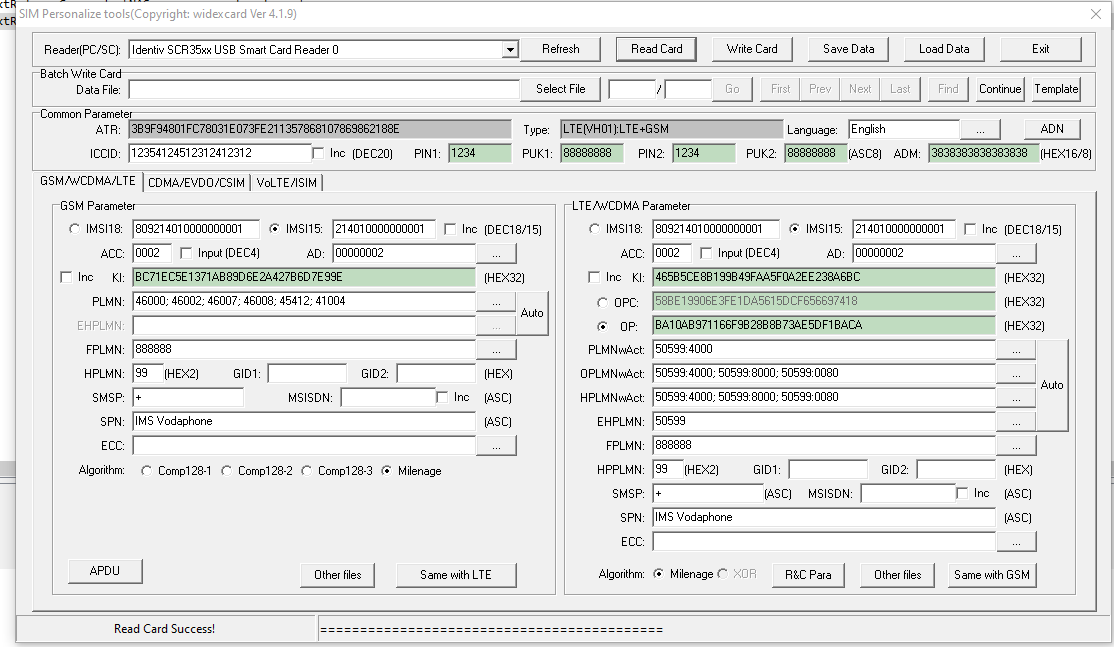

K – Subscriber Key

Subscriber’s secret key known only to the Subscriber and the Authentication Center (AuC/ HSS).

All the authentication rests on the principle that this one single secret key (K) known only to the USIM and the AuC/HHS.

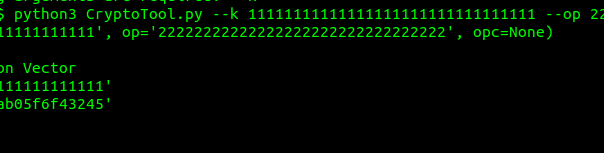

OP – Operator Code

Operator Code – same for all SIMs from a single operator.

Used in combination with K as an input for some authentication / authorisation crypto generation.

Because the Operator Code is common to all subscribers in the network, if this key were to be recovered it could lead to security issues, so instead OPc is generally used.

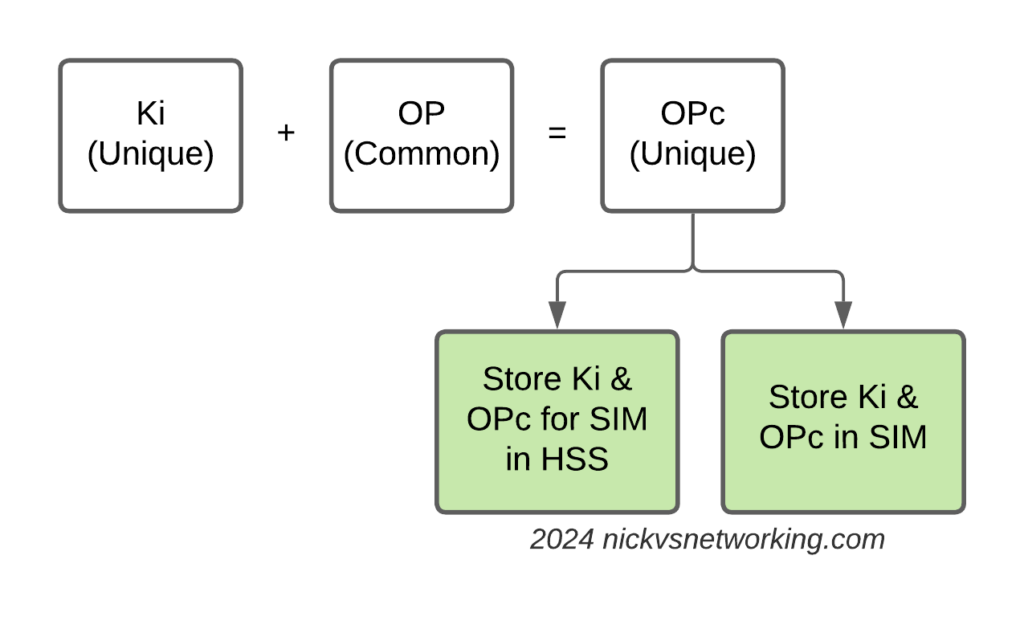

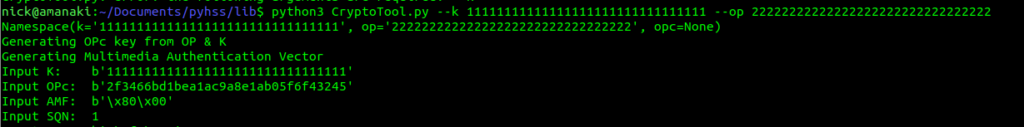

OPc – Operator Code (Derived)

Instead of giving each USIM the Operator Code a derived operator code can be precomputed when the USIM is written with the K key.

This means the OP is not stored on the USIM.

OPc=Encypt-Algo(OP,Key)

PLMN (Public Land Mobile Network)

The PLMN is the combination of MCC & MNC that identifies the operator’s radio access network (RAN) from other operators.

While there isn’t a specific PLMN field in most USIMs it’s worth understanding as several fields require a PLMN.

HPLMNwAcT (HPLMN selector with Access Technology)

Contains in order of priority, the Home-PLMN codes with the access technology specified.

This allows the USIM to work out which PLMN to attach to and which access technology (RAN), for example if the operator’s PLMN was 50599 we could have:

To try 4G and if that fails use 3G.

In situations where operators might partner to share networks in different areas, this could be set to the PLMN of the operator first, then it’s partnered operator second.

OPLMNwACT (Operator controlled PLMN selector with Access

Technology)

This is a list of PLMNs the operator has a roaming agreement with in order of priority and with the access technology.

An operator may roam to Carrier X but only permit UTRAN access, not E-TRAN.

FEHPLMN (Equivalent HPLMN)

Used to define equivalent HPMNs, for example if two carriers merge and still have two PLMNs.

FPLMN (Forbidden PLMN list)

A list of PLMNs the subscriber is not permitted to roam to.

HPPLMN (Higher Priority PLMN search period)

How long in seconds to spend between each PLMN/Access Technology in HPLMNwAcT list.

ACC (Access Control Class)

The ACC allows values from 0-15, and determines the access control class of the subscriber.

In the UK the ACC values is used to restrict civilian access to cell phone networks during emergencies.

Ordinary subscribers have ACC numbers in the range 0 – 9. Higher priority users are allocated numbers 12-14.

During an emergency, some or all access classes in the range 0 – 9 are disabled.

This means service would be could be cut off to the public who have ACC value of 0-9, but those like first responders and emergency services would have a higher ACC value and the network would allow them to attach.

AD (Administrative Data)

Like the ACC field the AD field allows operators to drive test networks without valid paying subscribers attaching to the network.

The defined levels are:

- ’00’ normal operation.

- ’80’ type approval operations.

- ’01’ normal operation + specific facilities.

- ’81’ type approval operations + specific facilities.

- ’02’ maintenance (off line).

- ’04’ cell test operation.

GID 1 / 2 – Group Identifier

Two group identifier fields that allow the operator to identify a group of USIMs for a particular application.

SPN (Service Provider Name)

The SPN is an optional field containing the human-readable name of the network.

The SPN allows MVNOs to provide their own USIMs with their name as the operator on the handset.

ECC (Emergency Call Codes)

Codes up to 6 digits long the subscriber is allowed to dial from home screen / in emergency / while not authenticated etc.

MSISDN

Mobile Station International Subscriber Directory Number. The E.164 formatted phone number of the subscriber.

This is optional, as porting may overwrite this, so it doesn’t always match up.

References:

https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/131100_131199/131102/12.05.00_60/ts_131102v120500p.pdf